‘Bio-Art’ Workshops To Show Creative Process Using Cochineal Insects, Bacteria

The intersection of art and biology is the focus of a workshop series this week on the Texas A&M University campus.

The “Bio-Art” collaboration between Texas A&M’s College of Performance, Visualization and Fine Arts and the Department of Biology includes using cochineal insects for dyeing textiles and using bacteria as paint. Both events have reached their space limitations with students and faculty attending.

The workshops spun out of Tianna Uchacz’s special topics course (VIZA 689) for graduate students — Global Histories of Materials, Techniques and Skilled Making — which combines art history and theory with hands-on exercises, including spinning, weaving and silkworm rearing.

“With our focus on fiber and textiles this semester, so many of the artifacts we talk about fall under the notion of craft rather than art because they involve skilled making, but also because there’s a measure of utility to them,” said Uchacz, assistant professor in the College of Performance, Visualization and Fine Arts, of the art-craft distinction. “We don’t think about clothing, fabric, textiles in the same way we think about paintings or sculpture. So we’re trying to dismantle this artificial division. I’m hoping my students — many of whom are in the visualization program — will think about the material world and its properties in ways that can help them design virtual objects and spaces.”

The “Dyeing with Cochineal Bugs” workshop, led by Naomi Rosenkranz of the Center for Science and Society at Columbia University, explores the “little red insect that changed the world,” Uchacz said. Textiles drove the global economy in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, and a lucrative part of the textile industry was dyeing, she said. A material source for a strong, colorfast and luxurious red was difficult to find. Cochineal — a parasitic insect that grows on the prickly pear cactus — changed all that.

“In the 16th century, all of a sudden the European markets were introduced to this new little bug from the Americas that had a much more concentrated red dye in it,” Uchacz said.

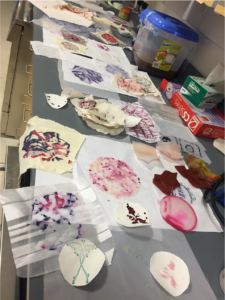

The dyeing methods remain similar to those in the early modern period, Uchacz said. The bugs are harvested and dried, and the dried cochineal are crushed, soaked in water and the dye is extracted with the help of heat. Any remaining cochineal parts are filtered out. Separately, the textiles (cotton, wool, silk) are mordanted with metal salts of aluminum, iron or copper, which not only allow the dye to adhere more permanently to the textiles but also affect the resulting color. The mordanted textiles are then heated in the cochineal dye bath and pick up the dye in different hues, she said.

“The color ranges from bubblegum pink to purple, depending on the mordant,” Uchacz said. “It’s as phenomenal a process today as it was 500 years ago.”

On Tuesday at the Conservation Lab in the Evans Annex, participants will prepare the cochineal dye and mordant their textiles, then dye the textiles on Thursday.

The “Printing With Bacteria” workshop will be led by Dr. Donna Janes of the Department of Biology in Room 205 in Heldenfels Hall. Uchacz said there is an established practice of using bacteria genetically modified to express color in art, featured notably in the American Society for Microbiology’s annual Agar Art Contest. On Wednesday, participants will paint bacteria onto agar in petri dishes, then put them into an incubator to grow. Friday, the bacteria will be transferred onto textiles, and a fixer will be applied to prevent washing away.

All participants will wear proper personal protective equipment and sign a consent form for lab safety guidelines.

Uchacz said she hopes participants will gain a better understanding of the longstanding relationship between artists and the natural world. Historically, artists were often proto scientists, she said, and their trial and error and material experimentation contributed toward the scientific method and the rise of empiricism.

“I want people to seek interactions between biology and art, and not be intimidated by the materials,” she said. “To remember that the natural world is partly a collaborator. Exposing students and colleagues to some of these historical or more recent art techniques is a reminder that art emerges from creative engagements with the natural world. The world is our palette.”

Top photo: Naomi Rosenkranz at Columbia University has led textile-dyeing workshops in which participants work with cochineal insects.