Why Public Art Matters

Researching public art’s rise to relevance and women artists’ struggle for equality

Public art, and its detractors, go hand in hand. An online search quickly reveals results like:

“Why Public Art is So Consistently Awful,” “What is the Point of Public Art if the Public Does Not Like It,” and others.

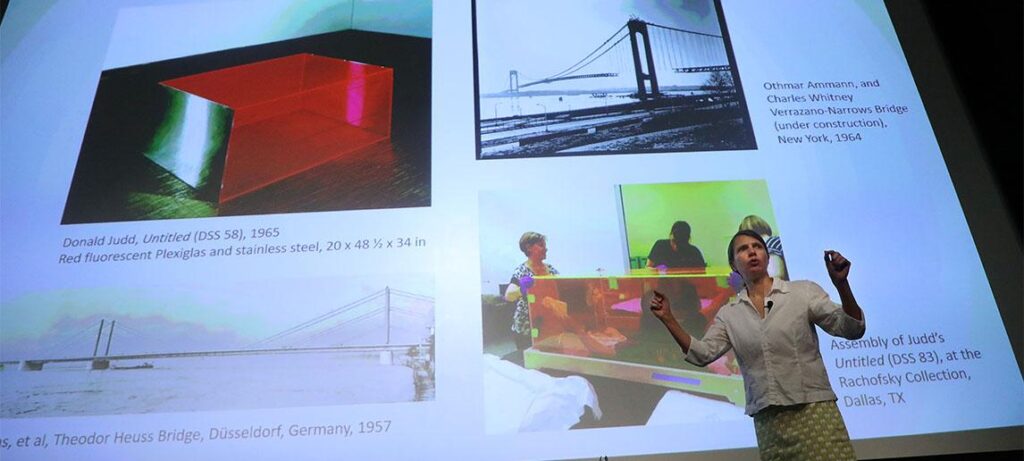

These aren’t new complaints, said Susanneh Bieber, an award-winning art and architectural historian in the Texas A&M departments of visualization and architecture whose research focuses on American artists of the 1960s.

That era’s artists were well aware that many view art as frivolous and elitist.

Art for Change

Bieber, who is writing a book about ‘60s art, said many of the era’s artists engaged with the built environment because they wanted to make their art more relevant to the general public.

Their effort worked.

Although plenty of public art naysayers remain, as reflected in those search results,‘60s artists were indeed able to significantly elevate public art’s relevance to the general public. They did something important — their art helped change how American society looks at “big picture” matters such as the Vietnam War. They showed that art can inspire a society to question the status quo and to critically reevaluate historical events from different perspectives.

Bieber’s research also reveals female artists’ previously unsung contributions as well as their struggles with art world sexism.

A New Way to Look at Sculpture

In the ‘60s, artists such as Claes Oldenburg began to reimagine the monument, a staple of public art for centuries. Monuments traditionally celebrate war victories or heroism in a vertical orientation — a man on a horse on a pedestal is a typical case.

Oldenburg had different ideas about monuments. He reimagined well-known structures such as the Washington Monument, for example, in a drawing of a giant pair of scissors pointed skyward. “Designs like these, which he never intended to be built, have a light-hearted touch but seriously rethink what a monument could be,” said Bieber. “He’s questioning society’s framework of what a monument is honoring, for whom and for what purposes it was built.”

Art as Protest

In 1969, as the U.S. war in Vietnam and antiwar protests in the U.S. raged, Oldenburg, supported by a group of Yale University faculty and students, built a monument that served as a protest against the war and as the centerpiece of a campus protest area.

The piece, “Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks,” was a tank made of painted plywood with an inflatable, lipstick “bullet” pointing skyward from its center. Placed overlooking the campus’ World War I memorial and the president’s office, the piece resists a simple interpretation, but like his Washington Monument/scissors drawing, it’s Oldenburg’s way of asking what values a monument reflects and how it perpetuates these values, said Bieber.

Another artist who rose to prominence in the ‘60s, Robert Smithson, also questioned monuments’ form and purpose.

Before his untimely death in a 1973 airplane crash, Smithson created sculptures for display in landscapes instead of indoors, sometimes using reflected materials and glass sheets — a departure from the white/gray surfaces of traditional monuments.

“Smithson’s pieces acknowledge different kinds of histories, not just the history of victory as told by white men, but histories that acknowledge pain, suppression, or environmental degradation,” said Bieber. “He influenced later artists, who further developed his artistic concepts.”

Then, in the ‘80s, the efforts of ‘60s artists led to something that changed society.

Art to Remember

In early 1981, Maya Lin, a 21-year-old architecture student at Yale, submitted what would become the winning entry in a national design competition for a Vietnam Veterans Memorial for the National Mall in Washington D.C.

Her design echoes the tradition- breaking work of Oldenburg, Smithson and their 60s contemporaries with its reflective, polished black granite instead of monuments’ traditional white limestone or marble, and its horizontal, not vertical, orientation.

“The monument, instead of making a heroic statement, honors those who died, acknowledges the cost of war, asks us to consider the arguments for war and the arguments against it,” said Bieber. “It’s not a ‘black and white’ statement.”